OEUVRE

Still Life by

Renee Radell

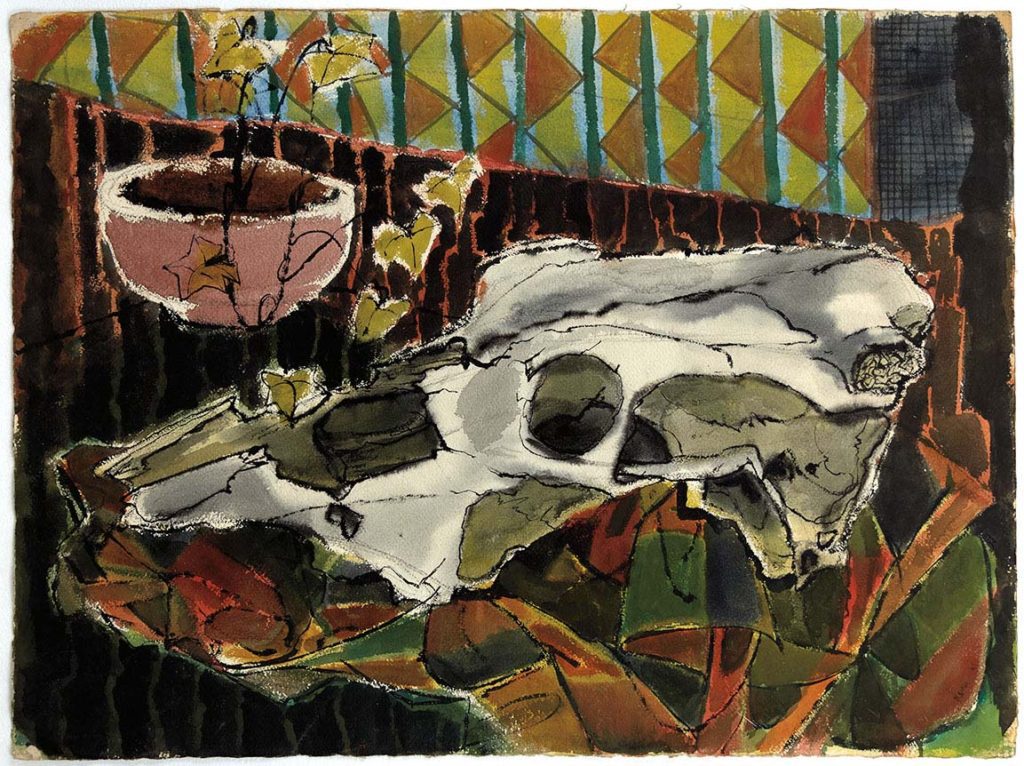

Renee Radell’s introduction to still life began by drawing flowers in vases on her basement walls in Detroit as a toddler, of course with parental encouragement. Like most artists with formal training, she began serious still life drawing and painting while attending the Art School of Detroit Society of Arts & Crafts. Ever resourceful, she marketed her water color paintings in art competitions. For example, Still Life with Fish won first prize at Detroit’s prestigious Scarab Club in 1952.

Social Commentary Settings

For Renee Radell, still life ranked high in her hierarchy of genres and she never abandoned it for extended periods during her career. She managed to incorporate it into some of her strongest social commentary paintings as a secondary subject matter. As an illustration, Relevantly Irrelevant was an anti-war statement about the Vietnam War and still life provided a setting in which to couch the artist’s visceral protest art.

Similarly, an excerpt from Renee Radell Web of Circumstance by Eleanor Heartney elucidates the artist’s painterly version of protest art with sociopolitical themes framed in still life settings

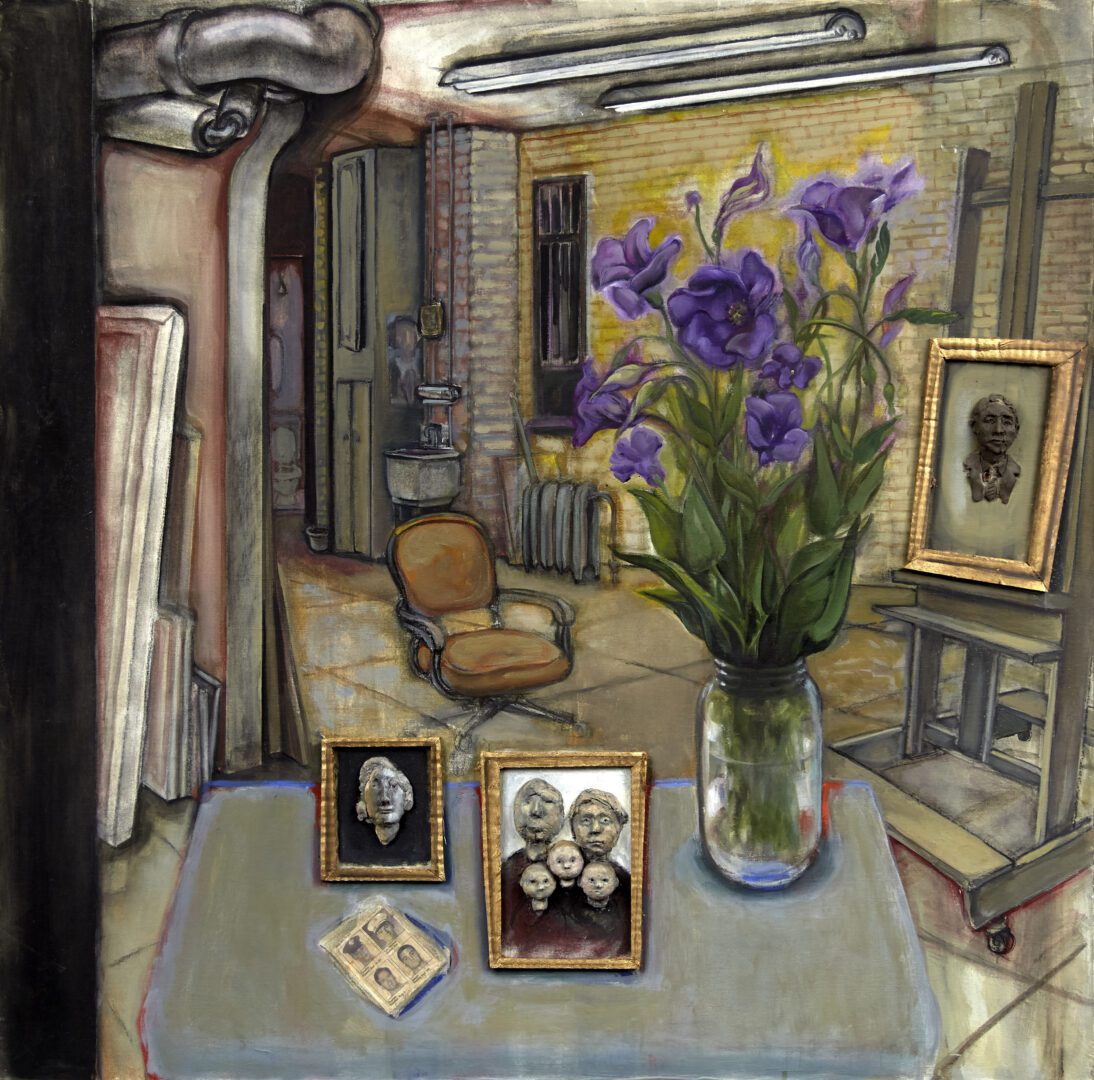

“Collage reappears in Relevantly Irrelevant (1972), which serves as a kind of memento mori for the Vietnam War. Here, a placid and lushly painted still life is interrupted by a photograph of a prisoner being transported through a North Vietnamese village in an ox cart. The work serves as a reminder of the strange schizophrenia that engulfs the populace when a war is conducted far away. It also puts the magnitude of war’s tragedy within the context of seemingly relevant everyday pleasures. There are echoes of this work in the much later Floral Tribute – 9-11 (2001), which was painted in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center. Here again, a vase of flowers on a studio table presents the deceptively peaceful setting for framed sculptural images that provide a more tangible dimension than a painted surface alone can offer to honor those who died when the towers fell.”

Still Life Surrealism

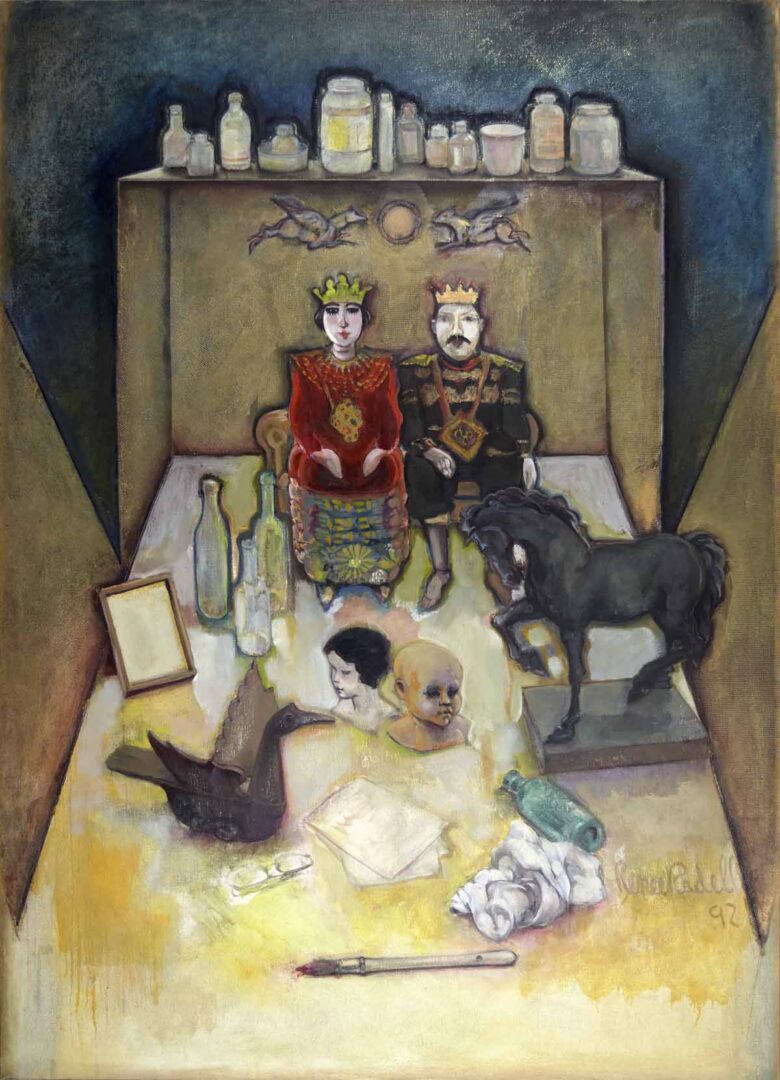

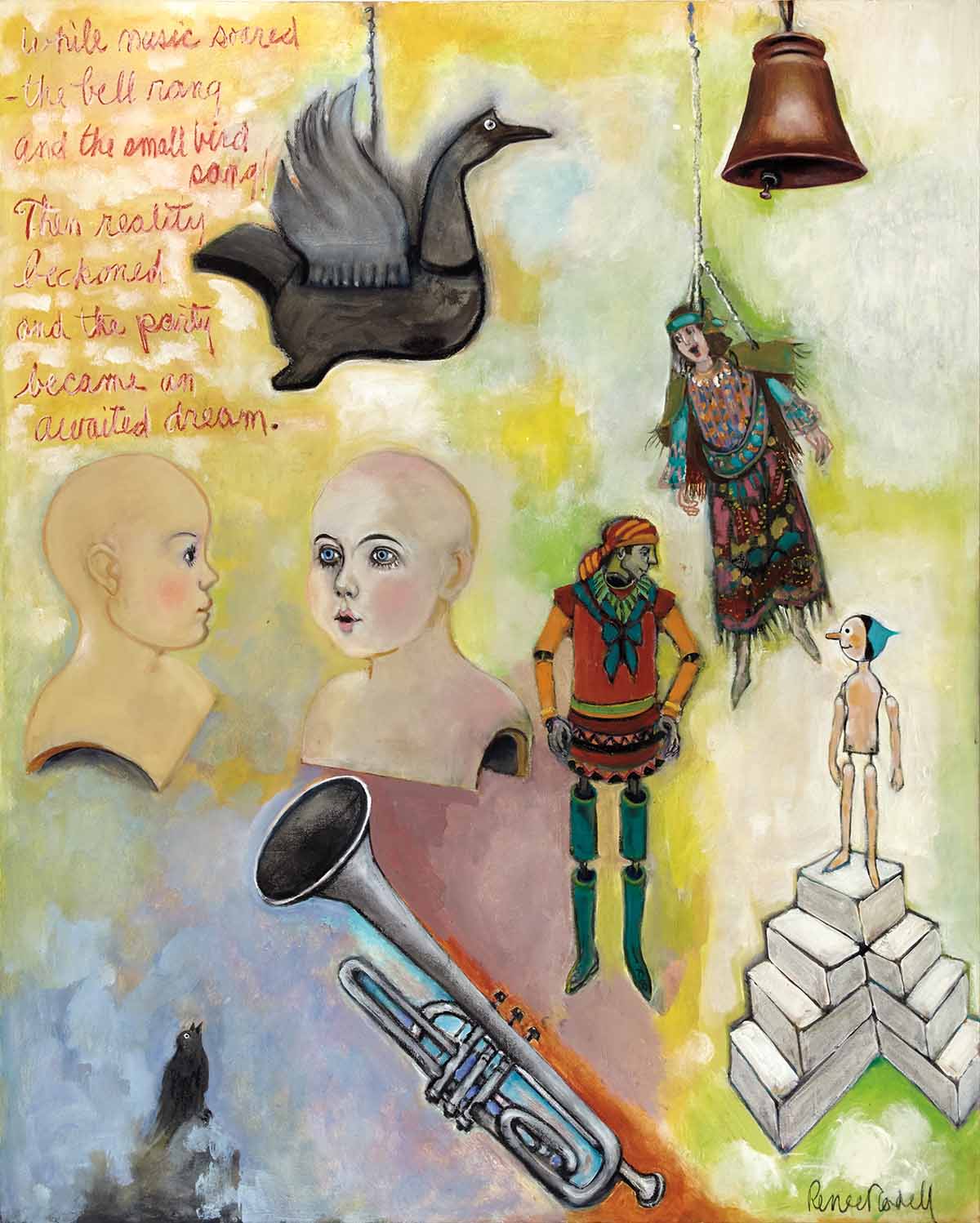

Still life regularly appears in Renee Radell’s allegorical work, nearly always venturing into surrealsim. This is not surprising for those who know that in the imagination of the artist, studio props have personalities and are capable of animation.

The Puppet House, for example, is an early “morality play” in which studio props come to life while “Reason [is] Held Hostage“. In nearly all paintings of this extensive series, inanimate forms participate, such as King and Queen with Court. Decades later, in Trial of Innocence a favorite doll reappears, symbolizing the vulnerability of youth, unprotected by law in a society suffocating in violence.

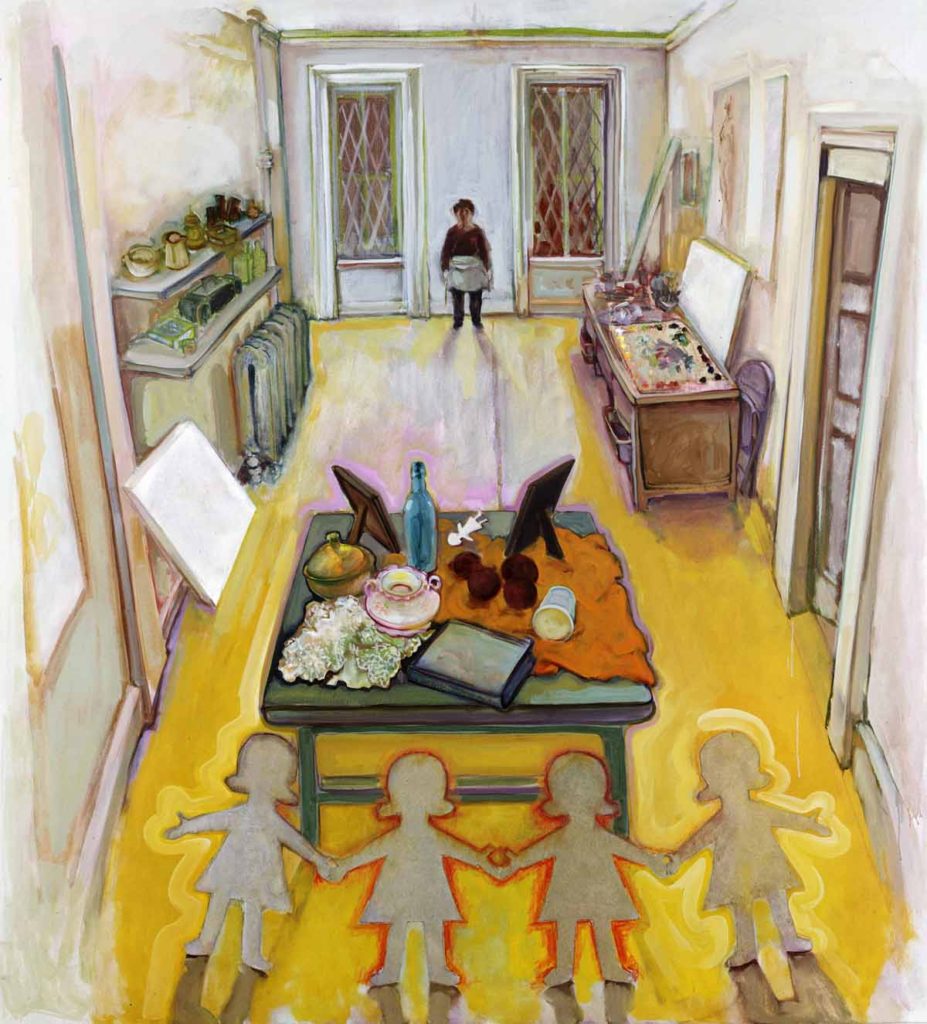

Decades later, the artist continues to include her studio comrades in picture after picture, enticing the viewer to participate in an imaginary world where life’s challenges are recast and somehow manageable. Recent delightful works such as Studio Still life with Pinocchio show her continual generation of powerful social commentary statements in inimitable artistic language while offering compendiums of some of her favorite studio objects – the wooden bird, the doll’s head, the puppets and the horse statuette that appear in other works.

In sum, still life for Renee Radell is a constant challenge, as portrayed in Confrontation on 28th Street. It provides a renewable platform for experimentation with new materials, new aesthetic challenges, and at times on which to convey profound philosophical ideas.